My first memory of Weedle was before she was born.

My heavily pregnant mother had gone to the hospital in

Orofino, Idaho for a checkup, and she was huge.

The doctor did an x-ray and found TWINS.

I was only 3, but remember how amazed my parents were.

They already had everything ready for one baby, but two?

Both of them were normal sized babies—I think Weedle was just under 7 lbs, and our brother was over 8 lbs!

Orofino was a lovely little idyllic town in North Idaho on the Clearwater River. It was in a deep valley, with hills seeming to go straight up on both sides. Many members of our mother's family lived there or nearby, and there was a warm welcome when the twins were born on June 25th, 1948.

I remember the first day Weedle walked—some weeks before our brother. She actually sort of trotted, smiling a big smile, both hands up in the air at her sides. She was so delighted with herself. To set the record straight, I gave her the name of "Weedle". Her full name was  Donna Louise Montre, and her twin, our brother, was Don Lee Montre. I think some of the family called her "Weezie", and I somehow devolved that to "Weedle", and it stuck.

Donna Louise Montre, and her twin, our brother, was Don Lee Montre. I think some of the family called her "Weezie", and I somehow devolved that to "Weedle", and it stuck.

When the twins were 2 and I was 5, we moved to Topeka to be near my father's family. Also—I remember long monologues by our father about how dangerous it would be for us to drive the "river road" when it was time to go to college at the University at Moscow, Idaho. Talk about planning ahead! I can't remember a time when it wasn't clear to all of us that college, whatever that was, was in our future!! I used to wonder if it was something like a little "cottage", or "cottage cheese", but was too shy to ask.

We arrived in Topeka just after the big 1951 flood, and it was hard to find a place to live. We ended up in a nice older house with big shady trees and a deep porch at 2017 Lane street. Brick sidewalks, brick streets. The Baughman's ice cream wagon would come every day—pulled by a horse!—and our mother let us stand on the curb and wait for it. You could hear the bell from far away, and I remember all 3 of us on the curb, leaning forward as far as possible without toppling over, to spot it.

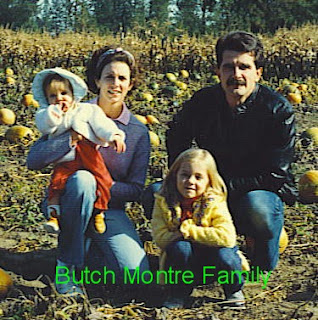

When we lived in that house, Weedle loved to collect locust shells in her little red wheelbarrow. It was heaping with them, and she would always say, "See how many I have?!" One time Butch, being a boy and full of mischief, dumped them out and she was heart-broken!! I remember Mama consoling her and scolding Butch. It was also in that house that once at dinner, Weedle was trying to be SO polite and grown-up and asked, "Please pass the catshit!"

We had a lot of fun at that house, even though we were only there for 2 years, I think. The yard was deep and shady, there was an alley, lots of foliage, and an old grape arbor—plenty of places for kids to play. When I was 8 and the kids were 5, we bought a new house—in a development of the type that were springing up all over the country, to accommodate veterans and their growing families. It was at 3429 Adams Street, in Highland Crest. It was just an ordinary rectangular box, but we were so excited about it! We would drive out nearly every evening to see how things were coming along. We each had our own room…the yard was a rough and bare former pasture, muddy, no grass, no trees. But we loved it. Weedle's room was pink, mine was blue, and Butch's was sort of gray.

and bare former pasture, muddy, no grass, no trees. But we loved it. Weedle's room was pink, mine was blue, and Butch's was sort of gray.

Anyway—it was a wonderful place to live, a neighborhood FULL of kids and dogs, no fences, and a feeling that things could only get better—a time of great optimism. In the summers we roamed the block, playing soft ball, kick the can, hide and seek, statues, and a game our mother taught us called "New Orleans" where you act things out—it was our favorite. Lots of times Weedle and I would work up little "shows" (only for the family), often involving dancing and me swirling her and flinging her about—she was really tiny, and I was tall and strong.

We had a piano in that house—an old upright—and we all took lessons. Our mother played and we would sing sometimes.

We both, Weedle and I, had a lot of good memories of living in that house and neighborhood. We didn't have a dog, but we had LOTS of "friend" dogs—Pootsie and Andy, for two. They practically lived with us, and we loved them.

When the twins started first grade, it was in East Avondale Grade School, a brand-new school a few blocks from home. We were the first kids to go there, and it was new and sparkling, new desks, new everything. It was light and bright. Weedle had a hard time leaving Mama, but got over it…she was always a "homebody", I think. There were lots of activities at the school, and I remember a talent show, sponsored by the PTA. All 3 of us had songs to sing. Butch was called first, and he stood up there on the stage, about 7 years old, and sang all 14 (or however many) verses of "Davy Crocket, King of the Wild Frontier". We had the sheet music at home, and Mama would play it while we sang. When it was Weedle's turn, her selection was—guess what—the same thing! I remember hearing a murmur of adults chuckling, and kind of wondering why.

Our parents often had us "perform" at that age. Every Saturday night, our paternal grandmother, "Gim", as we called her, and her sister, "Aunt Tu", would come over to watch TV. TV was still a new thing, and Mama would prepare snacks. Sometimes we would sing or play piano before the evening of TV began. We watched "Gunsmoke", "Have Gun, Will Travel", "Your Hit Parade", "George Gobel", etc. One evening the adults were wondering why Paladin of "Have Gun, Will Travel" didn't have a first name, and Weedle piped up, "He does!" When asked what it was, she replied, "Wire". Everyone thought that was pretty funny—his business card said, "Have Gun, Will Travel, Wire Paladin, San Francisco".

When the twins were about to enter 6th grade, our father decided we should move. We bought a house on the west side of Topeka, but it might as well have been in another country. All our friends, the people and places we had grown up with, were gone, and we were in a new unfriendly land. In our "old lives" we were known for being "the smart kids", we were confident and comfortable with our social station, our mother worked at the school as a cook, and was active in PTA, Girl Scouts, etc. Suddenly we were sort of "the poor kids", and no one knew us or treated us very well. Before long, though, the twins were established again as "the smart kids". At the spelling bee at Capper Junior High when they were in 9th grade, Weedle and Butch were the last two standing on the stage…we could never remember which one of them won!

I think we remained pretty much "outsiders" all the years we lived in that house on West 15th Street…but we had each other, thank God!! We used to congregate in our brother's room, where he would play records ("Listen to this—just for a minute!"). He loved Ray Charles and so did we. Weedle and I would often dance in front of the full-length mirror on the back of Butch's door. We spent MANY hours debating what was "cool"—white socks (NEVER), madras shirts and skirts (yes), etc. We were sort of fixated on that stuff for a couple of years. Weedle and I wore each others' clothes quite a bit, and would laugh about being the cool "Montre girls". In a way, we thought we were…in another way, we KNEW we weren't! We would lie awake at night (we shared a room) and play "word games" long into the night. Our poor mother, who had to get up very early, would come and ask us to keep it quieter, and we would TRY.

One memorable evening, Weedle and I decided to make "toothpick sculptures". We spent HOURS making very intricate, elaborate structures—we even kept them in our closets for a long time. We ran out of glue, so started using airplane glue—the odor drifted through the house and our brother woke up and had a fit! Mama came into the kitchen, and exclaimed, "Toothpicks! All over the floor!". We looked around and saw maybe two, so that made us laugh even more uproariously!! That phrase, "Toothpicks! All over the floor!", became one of our little "phrases" to use over the years.

I should have mentioned that our father died when the twins were 17 and I was 20. Our family had grown into sort of an armed camp. It was pretty terrible. Our father had been in a bomber shot down over Germany in WWII, and was severely burned—his face and hands, everything not covered by his flight suit. He lost an eye and was extremely disfigured, spent nearly 2 years in an Army hospital getting skin grafts, etc. He only weight 100 lbs. when his camp was liberated, and he had been a tall man, very handsome, black hair and blue eyes. He lost his teeth, and generally starved, nearly to death. His life, of course, was never the same. We, as kids, didn't really comprehend the pressures he was under, going into the public every day, etc. I know now that he also suffered from PTSD. At any rate, as the years passed and as we got older and more independent, things got worse for him, and he sort of turned on us and there came a point of no return. Our parents had separated a few months before he died. A few days before he died I went to see him, and he begged me to intervene and ask our moth er to take him back—I of course declined.

er to take him back—I of course declined.

Our father's death marked an end to a certain very controlled, rigid way of living, and everything just burst loose that had been so controlled. That summer of 1966, before she left for KU and began her "new life", we just lived wild, and loved it.

I'm not saying anything much about Weedle after she left—she always said her life sort of began when she went to KU…and in many ways it did. But—she used to like to talk with me about the times "before", when we were kids and adolescents. Also, of course, both she and I shared in the ensuing years things like marriage, kids, divorce, deaths of our brother and mother, our thoughts and feelings and triumphs. She was SO HAPPY during these recent years—I am very grateful for that. And she was ALWAYS there for me—I hope I was for her too.

Our mother was in a nursing home in Olympia, WA for just a few weeks before she died of a stroke on February 15, 1997. Weedle came out here while she was still pretty much OK, and Mama asked us to sing for her. Weedle and I both used to have such high, clear soprano voices that blended seamlessly—and in that nursing home room, we sang her every song she requested. I'm so glad we had that time!

And now—I'm the last one left. It reminds me of that "Farmer in the Dell" song, where at the end, "The Cheese Stands Alone". As a child, I can remember always wanting to be "The Cheese", but now that I am, it isn't that much fun. More than ever, I look forward to joining them all.